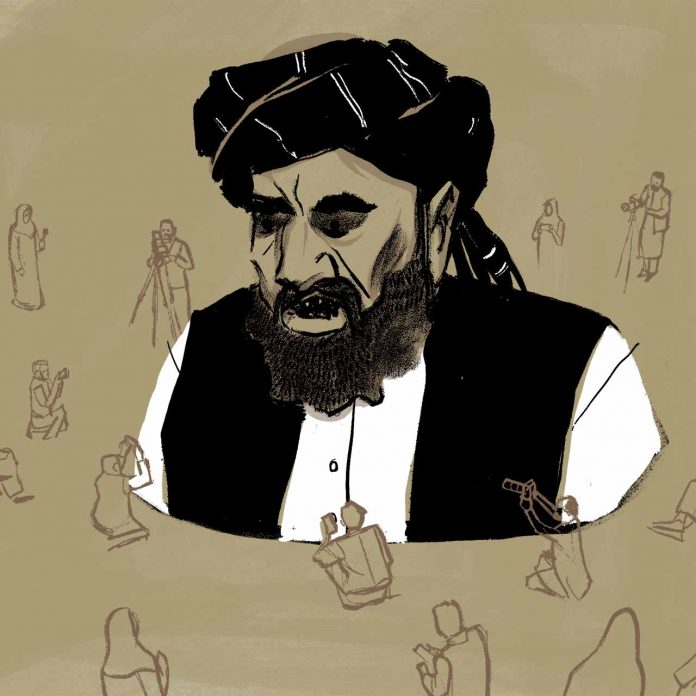

Taking risks and facing threats, they’re keeping Afghanistan’s decimated media alive.

Aweek after Taliban militants swarmed into the Afghanistan capital last August, journalist Hujatullah Mujadidi received an urgent email.

A French flight was available to get Mujadidi and his family safely out of Kabul the very next day, it said. Two more encouraging emails from the French embassy followed.

About this project

Hundreds of Afghan journalists fled after the Taliban takeover last year, but many more chose to stay in spite of the regime’s hostility. Masood Farivar, former chief of VOA’s Afghan Service, interviewed several about what drove them to their decisions, and how their work has changed in a culture of intolerance.

“Just bring what is strictly necessary: Light pack (sic) water and some food,” read the final one at 3:09 a.m.

Mujadidi, a prominent free press advocate, had just three hours to decide: Stay or go?

“On the one hand, I was thinking about my children and their futures,” Mujadidi said. “On the other, I was thinking about journalists calling, telling me I am their only contact.”

In the end, Mujadidi put journalism over family. And he wasn’t alone.

As the Taliban took power, scores of journalists, including some from VOA’s Afghan Service, fled for their safety in the face of a likely turn to media repression.

Yet many more chose to stick with their country and stand by their audiences.

Over the past several months, VOA spoke with journalists from across Afghanistan who decided to remain. They described a deep commitment to journalism and expressed hope that conditions would improve, despite some recent setbacks.

Taliban fighters walk toward journalists during a protest in Kabul on December 28, 2021. (AFP)

Those include Taliban orders to not carry foreign-produced news or entertainment shows and the detention, and sometimes beating, of journalists who defied their directives or censorship.

How much better – or worse – it might get is anyone’s guess.

“In the past three to four months, my optimism has dampened,” said Khpalwak Sapai, director of the popular TOLOnews, which has had to rebuild its staff since August.

“I’m not certain how much longer the independent media can survive.”

And the ranks of female journalists, who flourished before the takeover, were hit hard.

“A lot of the female journalists in Afghanistan, their families did not allow them to return to work,” said investigative reporter Mina Habib, who turned down a chance to leave.

Before the Taliban takeover, more than 600 media outlets operated in the country, employing some 5,000 journalists, according to a joint report by the International Federation of Journalists and Afghanistan National Journalists Union.

By February, that figure had more than halved.

Any comeback faces big obstacles.

Taliban spokesperson Zabihullah Mujahid did not respond to VOA’s messages requesting comment for this article. Mujahid and other Taliban officials have said they don’t object to independent media – but only if they operate within the bounds of Islamic law.

A Taliban commander speaks to members of the media after they halted a demonstration by women protestors happening in front of a school in Kabul on September 30, 2021. (AFP)

In September, the Taliban released “11 rules of journalism” that discourage reporting that “could have a negative impact on the public’s attitude or affect morale.”

Across the country, local Taliban officials require journalists to clear stories with them.

“This can call into question a media outlet’s independence and can lead to self-censorship,” said Qutbuddin Kohi, a senior reporter with Pajhwok Afghan News.

So reporting becomes a balancing act – and a fall can be dangerous.

Kohi said he’s free to report on poverty and unemployment. Not so with the Taliban’s persecution of former government officials.

“That,” he said, “would put my life in danger.”

Source: VOA News| Brian Williamson