10/08/2022 Issue 15 Somali Magazine is Out today

Due to a severe drought and rising food prices brought on by the Ukraine crisis, millions of people in Somalia may face hunger.

The worst drought in decades is ravaging East Africa, destroying crops and driving the cost of food out of reach of many. In Somalia alone, 7 million people (out of a total population of 16 million) could be at risk of famine in the next two months if aid is not scaled up to meet skyrocketing needs.

In 2011, some 250,000 people in Somalia—half of whom were children—died in a famine that followed three consecutive seasons without adequate rainfall. Less than half the aid that donor countries pledged to the humanitarian response was actually funded, making many of those deaths preventable.

As Somalia enters its fifth consecutive season without enough rain, world leaders must step up to save lives. The 2022 humanitarian response plan for food security in Somalia is currently only 20 percent funded—this at a time when the growing impacts of climate change have damaged livelihoods and the crisis in Ukraine has spiked the cost of food and the fuel needed to deliver it. As a result, 230,000 Somalis are already living in famine conditions.

“We have had to drastically reconsider our operations due to the sharp increase in prices and fuel over the last few months,” says Hashi Abdi, supply chain manager for the International Rescue Committee (IRC) in Somalia. “When we do not have enough medical supplies in our clinics, we have to turn away the increasing number of patients who are in need of critical care and support.

This is happening all the more frequently as lifesaving aid is diverted to help Ukraine—leading to an even more drastic reduction in the aid we can deliver.

“As ever, this crisis is impacting the most vulnerable,” says Abdi. “Without immediate international funding, a catastrophic famine is undoubtedly on the horizon for Somalia and the region as a whole.”

Conflict and other complications

Somalia has seen three decades of conflict, destabilizing communities. Indeed, Somalia currently produces less than half the amount of food it did before its civil war began in the early 1990s, forcing the country to become increasingly dependent on food imports and highly vulnerable to supply chain disruptions and fluctuations in global food prices, such as those exacerbated by the crisis in Ukraine.

Conflict in neighboring Ethiopia has also emerged since 2020, overlapping drought and stretching the entire humanitarian response to the region. In Somalia, pockets of conflict remains active and, as the drought deepened, nearly 900,000 people are living in unstable areas. Many people have already tried to leave these areas, but those who remain are largely inaccessible to humanitarian organizations.

Failure in mitigation and response

The Somalia government issued a Drought Declaration in April; however, humanitarian aid pledges from donor countries have not translated into significant funding and a scale-up of aid to date.

Even once new U.S. funding announced this week is fulfilled, the humanitarian response plan for the region would be funded at just 40 percent.

Funding shortfalls are explained in part by the international focus on the war in Ukraine. The $1.9 billion appeal for the humanitarian response in Ukraine was 85 percent funded in just over three months. Donors raised $16 billion for wider efforts to support Ukraine within a month, demonstrating the capacity for resource mobilization when the political will exists. Yet the countries experiencing the ripple effects of the Ukraine crisis have fallen off the radar.

Somalia’s drought leaves nearly a million people desperate with hunger.

Overlooked due to the war in Ukraine, the humanitarian crisis in Yemen, and the conflict in neighboring Ethiopia, Somalia is dealing with one of its worst droughts in four decades.

Nearly a million people have left their homes in search of food, water, and humanitarian assistance in towns and major cities.

Dolow, a border town in Somalia’s southwestern region of Gedo which has been hosting thousands of families displaced by the 2011 drought, is now receiving drought-affected people in their hundreds daily, some coming as far as 300 kilometers (186 miles) on foot or riding donkeys.

Farhiyo Ahmed and her seven children left the town of Ufurow and reached an internally displaced persons (IDPs) camp in Dolow, a journey that took them 18 days.

She told Somali Magazine that the drought has devastated her town, small farm, and livestock.

“I came here because we lost everything we have and I couldn’t find another way to feed my children. But coming here wasn’t an easy task. I came here seven days ago and haven’t received any humanitarian assistance so far,” she said.

She said the people in the camp find themselves in a very difficult situation as they don’t have shelter, food, or water, not to mention access to education.

The vast number of people who reached Dolow as a result of the drought, which hit 90% of the country and has affected half its population, are women and children.

Muhibo Ali Hilowle, 57, a mother of nine, told Somali Magazine at the internally displaced persons camp in Dolow that she hasn’t seen a drought as bad as this one in her entire life.

She said her children are hungry and she’s very concerned.

“As an adult, I am adapting by not eating but drinking a lot of water, but the children are starving. They haven’t eaten in at least two days.”

Saruuro Bishaar Abdi is a newcomer to the camp. She fled from Raahole, a town in the Baay region.

She said she walked for a week to reach the camp with her 10 children.

“The drought has killed all my livestock, which was our only means to survive and feed my children. When all of them died and I wasn’t able to get a job, I made up my mind to come here to get a better life,” Abdi said.

Ali Abdikarim, a father of four who fled from the town of Luuq, an eight-hour drive from Dolow, said he was told by a friend that humanitarian agencies are helping drought-affected people, but they haven’t received any help so far.

Sacdiyo Yacqub, 27, a mother of five children aged between one and 10, told Somali Magazine while crying that she and her children haven’t had a meal for a week.

“We have nothing. There are no jobs. There is no food, running water, toilets or shelters, anything. I have been keeping my head high, but this is unbearable. We haven’t eaten for eight days, except what our neighbors send us and leftovers,” she said.

Visit

Somalia’s special presidential envoy for the drought response and humanitarian issues, Abdirahman Abdishakur Warsame, and the UN humanitarian coordinator for Somalia, Adam Abdelmoula, recently visited the camp and raised the alarm, saying this is the worst drought in Somalia’s recent memory.

Warsame, who spoke to Somali Magazine at an IDP camp in Dolow, said Somalia and the international community must work together to avert famine and to help the families affected by the drought and called for urgent humanitarian intervention.

“I’ve been traveling to different places and towns to see the effect that the drought has had on people. A week ago, I visited Buloburde. Before that, Baidoa, and now I am in Dolow to see the situation of affected people here,” he said.

Warsame said his responsibility is to organize and work with humanitarians to lift any restrictions.

He said what he has seen at IDP camps in Dolow is a humanitarian crisis at its worst and it is time to act to avoid famine.

Abdelmoula told Somali Magazine that Somalia is seeing its worst drought in recent memory.

“The people who are living here now came in recent days and weeks and have since been living without humanitarian assistance,” he said.

Human and Animal loss

When Somali Magazine asked about the human loss due to the prolonged devastating drought, Warsame said the authorities in Dolow told him that at least 60 people had died.

Abdelmoula said eight districts in Somalia are now facing famine-like conditions and 366,000 people in the country will die by September if humanitarian assistance is not scaled up as soon as possible.

He noted that 7.1 million Somalis — nearly half the country’s population — are in need of humanitarian assistance and 1.5 million children are severely malnourished.

“If we don’t act now, thousands will die, and any delay is not an option to immediately save lives,” he told Somali Magazine.

Health impact

Dr. Mamunur Rahman Malik, head of mission and World Health Organization (WHO) Representative for Somalia, told Somali Magazine that the health consequences of the drought are causing alarming pain and suffering to the people affected.

“If we do not prioritize health in terms of expanding access to emergency health care and life-saving support, people will eventually die of diseases,” he said.

He said what they have seen in the drought and the famine-like situation in Somalia is that there is always a “disease between hunger and death and between malnutrition and diseases.”

“We feel that people will die of diseases more than hunger if we do not protect their health,” he said, adding that people owing to the food insecurity situation will be more vulnerable to diseases and malnutrition as their ability to prevent infections will be low.

“We need to protect the health of these vulnerable people to save their lives from causes that are largely preventable. We are seeing a high number of cholera, acute diarrheal disease, pneumonia and measles cases amongst these vulnerable people impacted by the drought,” he added.

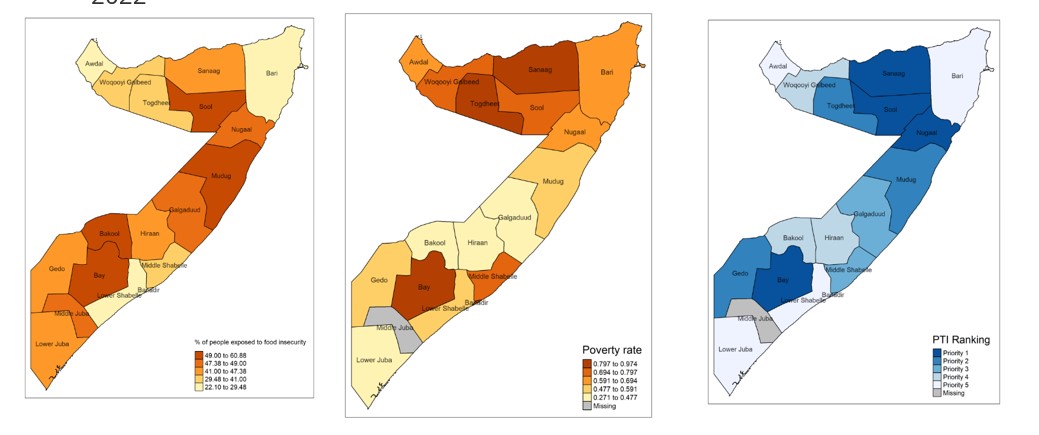

Mapping climate change and drought in Somalia

| A) IPC Acute Food Insecurity Situation July – Projection for April – June 2022 | B) Monetary poverty estimates | C) Priority areas to mitigate the adverse impact of the recent drought on the poor |