Facebook Twitter (X) Instagram Somali Magazine - People's Magazine

Before sunrise, small groups of women quietly leave displacement camps on the outskirts of Kismayo in southern Somalia. They walk together for hours into nearby rural areas where acacia trees grow in scattered clusters. Their goal is to collect acacia seeds, locally known as abqo, which have become a vital source of income for families who lost everything to drought and displacement.

For more than 100 displaced women in Kismayo, harvesting and selling these seeds is one of the few ways left to earn a living. The seeds are used as animal feed and are especially valuable during dry seasons when pasture is scarce. Buyers include pastoralists from rural areas who depend on them to keep their animals alive.

Abdiyo Hassan Ali, a 55-year-old mother of eight, is one of the women who rely on this work. Each day, she walks up to six hours to reach the acacia trees and return to town with her harvest. She sells the seeds at a small market near Kismayo’s livestock holding area, where traders buy them and resell them to herders.

Her daily earnings are small but meaningful. On a good day, she makes three or four dollars. From that amount, she spends most of the money on food, water, and firewood. Despite the struggle, this income has helped her family regain a sense of stability after months of hardship.

Abdiyo and her family were forced to flee their village in Lower Juba in late 2022 after a severe drought killed nearly all their livestock. Like many others, they settled in Nasrudin displacement camp. Life there was extremely difficult at first, with frequent hunger and no money for school. Since she began selling acacia seeds three months ago, her situation has slowly improved. She can now provide more regular meals and has enrolled four of her children, including two young girls, in a local primary school.

To pay school fees, she saves a small amount each week. Having a steady, even if modest, income has also helped her build trust with local shopkeepers, who sometimes allow her to buy food on credit when sales are low.

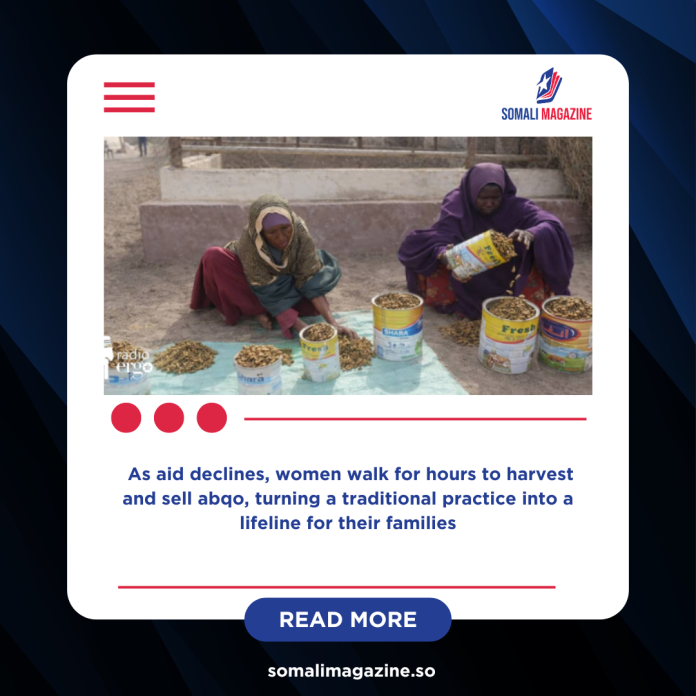

The acacia seed trade is seasonal, and prices change depending on availability and demand. Seeds are measured using recycled containers such as milk tins, which serve as standard units in the market. A single tin usually sells for around one and a half dollars, though prices may drop when supply is high.

Harvesting the seeds is not easy. The trees are tall, and the women must work together. Using long sticks, they shake the branches so the seeds fall to the ground, then collect them into sacks. They travel in groups for safety, as the areas they pass through are remote and sparsely populated. Despite the risks, the women say they feel protected and rely on each other for support.

At the market near the livestock yard, dozens of women sit under the harsh sun, waiting patiently for buyers. For many, the market has become more than a place of trade. It is also a space of shared experience, where women affected by drought and displacement find solidarity.

Another seller, 45-year-old Fadumo Abdulle Hassan, supports three children on her own. After separating from her husband, she struggled to survive. She began selling acacia seeds last year, walking more than 20 kilometres into the bush and returning with heavy sacks balanced on her head. The work is exhausting, but it provides food for her family.

Before this, Fadumo tried running a small ice cream business, but it failed because unsold products would melt and go to waste. Acacia seeds, however, do not spoil quickly, allowing her to sell them another day if buyers are few.

The trade in acacia seeds has existed in rural Somalia for many years. However, for displaced women in Kismayo, it has become increasingly important as food aid to camps has declined. With fewer handouts available, women are being pushed to find their own ways to survive. For many, these small seeds now represent dignity, resilience, and the hope of feeding their families one more day.